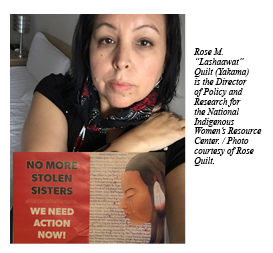

The Federal Trust Responsibility and MMIW

Native women deserve a basic right to human safety.

The United States government has a longstanding federal trust responsibility to assist Indian tribes concerning the health, safety and welfare of their citizens. As recognized by many international experts, violence against Indigenous women is a serious human rights violation─a violation so significant that it precludes their realization of all other human rights.1 Yet, for hundreds of years, federal officials have flagrantly disregarded the federal trust responsibility entrusted to them concerning Indian tribes, leaving Native women unprotected and imperiled. As primary targets since colonization, Indigenous women have faced an ongoing spectrum of horrific violence ranging from domestic and dating violence to murder, trafficking, and rape. Confronted with the highest rates of violence in the Nation, tribal leaders have continued to decry the federal government’s inability to discharge their duties to uphold their sacred, solemn commitment to Indian people and safeguard the lives of Indian women.

“The murders and disappearance of women and girls in Alaska Native and American Indian communities are connected to the lack of protections from the state and federal government and the failure of the federal government to provide resources to establish a comprehensive response.”─Catherine Moses

The Federal Trust Responsibility and Indian Tribes

The federal Indian trust responsibility is a legally enforceable fiduciary obligation under which the United States “has charged itself with moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust” toward Indian tribes.2

Each federal department has a written policy articulating this responsibility. The Department of Health and Human Services recognizes the federal trust responsibility in this way:

Since the formation of the Union, the United States (U.S.) has recognized Indian Tribes as sovereign nations. A unique government-to-government relationship exists between Indian Tribes and the Federal Government. This relationship is grounded in the U.S. Constitution, numerous treaties, statutes, Federal case law, regulations and executive orders that establish and define a trust relationship with Indian Tribes. This relationship is derived from the political and legal relationship that Indian Tribes have with the Federal Government and is not based upon race.3

Further, the Bureau of Indian Affairs provides:

The federal Indian trust responsibility is… a legally enforceable fiduciary obligation on the part of the United States to protect tribal treaty rights, lands, assets, and resources, as well as a duty to carry out the mandates of federal law with respect to American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and villages. In several cases discussing the trust responsibility, the Supreme Court has used language suggesting that it entails legal duties, moral obligations, and the fulfillment of understandings and expectations that have arisen over the entire course of the relationship between the United States and the federally recognized tribes.4

––––––––––

1 E/2013/27- E/CN.6/2013/11 Para. 10

2 Seminole Nation v. United States, 1942.

3 See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tribal Consultation Policy https://bit.ly/3cMxbnY

4 See U.S. Department of Interior at https://on.doi.gov/3tyASUb

Court decisions make clear that the entire federal government is blanketed by the trust responsibility, and that every federal agency, not just the Bureau of Indian Affairs, must fulfill the trust responsibility in implementing statutes.5

It is a duty, a solemn oath that the United States made with Indian Tribes during the era of treaty-making. It is a duty of protection that our Ancestors understood.

The Federal Trust Responsibility and the Safety of Indian Women

In support of the movement for change and built upon the blood, sweat, and tears of grassroots advocates and tribal leaders, Congress enacted several pieces of legislation signaling support to tribal self-determination and the safety of Native women.6 The VAWA 2005 reauthorization included a historic Safety for Indian Women Title, which recognized the unique legal relationship of the United States to Indian Tribes and Native women. Congress created Title IX “to strengthen the capacity of Indian tribes to exercise their sovereign authority to respond to violent crimes committed against women.”7

Moreover, in recognition of its trust obligation, VAWA Title IX, Section 901 provides that “the federal government has a trust responsibility to assist tribes in safeguarding the lives of Indian women”8 (emphasis added). And in the fight for the 2013 VAWA reauthorization, Congress legislated a partial Oliphant Fix. Under VAWA 2013, Congress recognized and affirmed the inherent sovereign authority of Indian tribes to prosecute non-Indians for dating and domestic violence and qualifying protection order violations committed on tribal lands.9 Although the full reach of tribal jurisdiction was limited by Congress—such as stalking, sexual assault by a stranger or acquaintance and sex trafficking— VAWA 2013 was a historic amendment affirming tribal sovereignty and reaffirming the federal government’s commitment to addressing violence in tribal communities. VAWA 2013’s limited reaffirmation of tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians, known as Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction (SDVCJ), “fundamentally changed the landscape of tribal criminal jurisdiction in the modern era.”10

Tribal grassroots activism led the movement locally and nationally to not only raise awareness but to also legislate for change regarding the devastating rates of violence committed against Native women. Over the years, a series of studies revealed shocking rates of violence against Native women. A study by the National Institute of Justice under the USDOJ revealed alarming rates of violence,11 with findings that show American Indian and Alaska Native women experience severe rates of lifetime violence, including:

- 56.1% who have experienced sexual violence;

- 55.5% who have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner;

- 48.4% who have experienced stalking; and

- 66.4% who have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner.12

Native women also experience homicide at higher rates than most of their counterparts. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Native women are murdered at a rate of 4.3% per 100,000 population, while their white counterparts experience homicide at a rate of 1.5%.13 The CDC also confirmed long held beliefs by tribal domestic violence advocates: almost half of Native victims were murdered by an intimate partner.

Another study by Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) provides that, “no research has been done on rates of such violence among American Indian and Alaska Native women living in urban areas despite the fact that approximately 71% of American Indian and Alaska Natives live in urban areas.”14 As a result of the gaps in data, UIHI focused a study aimed at assessing the number and dynamics of cases of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls in cities across the United States.15

Although these numbers do not tell the whole story, we can glean the effect of the devastatingly complex legal framework and various intersections that Native survivors of violence must confront. It is also in these numbers that we are able to fully grasp the failure of the federal government to completely fulfill its federal trust responsibility to tribes, families and most importantly to Native women.

––––––––––

5 See Parravano, 70 F.3d at 546 ("This trust responsibility extends not just to the Interior Department, but attaches to the federal government as a whole."); Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe of Indians v. U.S. Dept. of Navy, 898 F.2d 1410, 1420 (9th Cir. 1990); Nance v. EPA, 645 F.2d 701, 711 (9th Cir. 1981); N.W. Sea Farms, 931 F. Supp. at 1519 ("This [trust] obligation has been interpreted to impose a fiduciary duty owed in conducting 'any Federal government action' which relates to Indian Tribes." (quoting Nance, 645 F.2d at 711)).

6 The Tribal Law and Order Act and the Reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act 2000, 2005, 2013.

7 Agtuca, Jacqueline, “Safety for Native Women: VAWA and AmericanIndian Tribes” pg. 15 (2015).

8 2005 VAWA § 901 Findings.

9 25 U.S.C. § 1304.

10 National Congress of American Indians, VAWA 2013’s Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction Five-Year Report (March 20, 2018). 11 Department Of Justice, Nat’l Inst. Of Justice, Violence Against American Indian And Alaska Native Women And Men: 2010 Findings From The National Intimate Partner And Sexual Violence Survey 26 (May 2016), https://bit.ly/3pVHols

12 Id.

13 Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, Fowler KA, Jack SP, Lyons BH. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Homicides of Adult Women and the Role of Intimate Partner Violence — United States, 2003–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:741–746.

14 Lucchesi, Annita and Echo-Hawk, Abigail; Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls: A snapshot of data from 71 urban cities in the United States.

15 Id.

Challenges and Barriers for the Safety of Indian Women and the Federal Trust Responsibility

Despite the federal government's trust responsibility to tribes, both Congress and the Supreme Court have eroded the jurisdictional authority of Indian Nations, infringing on the ability of tribal governments to fully protect their citizens, including Native women brutalized by domestic, dating and sexual violence, stalking, trafficking and murder. Many Native women fear they, along with their children, will experience violence throughout their lifetime because of the longstanding barriers to recourse and justice that is their reality.

In addition to longstanding government sanctioned violence and a series of crippling tribal policies promoting paternalism, assimilation, relocation, termination and genocide of Indian people and Native women, there remains a set of laws and policies on the books, including but not limited to the Major Crimes Act, Public Law 280, the Indian Civil Rights Act, the Marshall trilogy16 and the Oliphant decision. These far-reaching legal barriers deeply entrenched in federal Indian law continue to endanger the lives of Native women.

The two main federal statutes governing federal criminal jurisdiction in Indian country are the General Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1152, and the Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1153. Section 1153 gives the federal government jurisdiction to prosecute certain enumerated offenses, such as murder, manslaughter, sexual abuse, aggravated assault, and child sexual abuse, when committed by Indians in Indian country.17 Section 1152 gives the federal government exclusive jurisdiction to prosecute most crimes committed by non-Indians against Indian victims in Indian country.18

Although armed with the jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute crimes committed against Native women, many, if not most U.S. Attorneys charged with doing so, failed to uphold their role in fulfilling this important responsibility. About 65 percent of criminal investigations opened by the FBI in reservations were referred for federal prosecution, according to a 2016 TLOA report.19 Of the 680 investigations that were closed without referral for prosecution, one of the most frequent reasons was due to insufficient evidence to determine whether a crime occurred.20

“We are going missing, we are being murdered. We are not being taken seriously. I am here to stress to you we are important and we are loved and we are missed. We will no longer be the invisible people in the United States of America, we have worth.”—Kimberly Loring Heavy Runner21

When a Native Woman Goes Missing

When a Native woman disappears and goes missing, so much of the “response” is based on numerous questions and challenges including which law enforcement agency has jurisdiction to take an initial report, the response, the search, detainment, the investigation and ultimately prosecution authority. The first 24 hours of any missing person case is a crucial time for law enforcement to organize and conduct an immediate search, but too often, questions of jurisdiction impede a timely law enforcement response. Unfortunately in most cases, the response of law enforcement is non-existent or wholly inappropriate. This can leave the responsibility of a search effort to the family members or tribal community.

The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women is a direct result of limitations placed on tribal authority to prosecute non-Natives for crimes committed on tribal land including the unconscionable resource disparities regarding public safety. The link to the de-evolution of federal Indian law and policy and failure of the federal trust responsibility cannot be denied. The current legal framework fails to respond to the disappearance and murder of Native women because that same framework was born during an era of termination of Indian tribes. Tribal leaders often speak of a “broken system,” but the truth is that the legal framework was not designed to protect Native women. Rather, it was built to fail them and further the continuation of paternalistic policies, colonization, and systemic genocide.

The sheer scale of the violence resulting in MMIW with the groundswell of survivor families, advocates and tribal leaders, and the abysmal failure by the government to adequately address it, partially explains why the MMIW issue has reached national attention and action. That is why tribal self determination and sovereignty must continue to be restored with adequate resources provided to implement tribally based solutions for the protection, safety and healing of their citizens and Native women, who stand as the heart of their nations.

––––––––––

16 Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832); Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831); Johnson v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823).

17 U.S. Department of Justice: Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions 2018 Report, https://bit.ly/3pXGLI4

18 The exception to this exclusive jurisdiction is set forth in 25 U.S.C. 1304, which recognizes the inherent power of a participating tribe to exercise special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction.

19 U.S. Department of Justice: Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions 2016 Report, pg. 10, https://bit.ly/2YZOZUa

20 Id. at 13.

21 Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. Oversight Hearing on Missing and Murdered: Confronting the Silent Crisis in Indian Country. Dec. 12, 2018. 115th Cong. Washington. 2018. (Testimony of Kimberly Loring Heavy Runner).