Stories are our Medicine

Reconnecting with Indigenous Teachings to Create Healing Spaces with and for Native 2SLGBTQ Survivors of Violence

Teachings across Indigenous cultures affirm that all individuals have a place in our societies and should not be abused, feared or excluded because of their gender identity or sexual orientation. Colonization challenged these teachings, imposing foreign norms that resulted in domestic and sexual violence and loss of life, and in thoughts and behaviors that isolate and intimidate. We remember and honor those who have lost their lives and dedicate these words in their names.

Please note: The content in this article may be triggering to some relatives. If you need assistance, contact StrongHearts Native Helpline at 1-844-762-8483 or via chat at strongheartshelpline.org.

A few months ago, in partnership with the La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians Avellaka Program Rainbow of Truth Circle, the National LGBTQ Institute on Intimate Partner Violence, and the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, NIWRC organized Conversations with the Field (CWTF) to develop a toolkit. The toolkit’s purpose is to help families and friends reconnect with Indigenous teachings and create healing spaces with and for 2SLGBTQ victims-survivors of domestic violence. Available resources fall short of meeting the needs of victims of domestic and sexual violence, as the StrongHearts Native Helpline found with the development of their resource database showing fewer than 300 Native resources and less than 60 Native shelters as compared to the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s 4,000 resources and 1,500 shelters. Resources for Indigenous 2SLGBTQ victims of domestic and sexual violence are even fewer, so helping families and friends support their 2SLGBTQ relatives and friends who experience domestic and sexual violence is even more important.

An Advisory Committee of CWTF participants continued to develop the toolkit, expected to be released by early next year and agreed that it would be helpful to include stories in the toolkit. They share their experiences like different streams coming together as a river for healing. Together we are stronger, and we will carve out healing spaces just as water carves the land it flows through. These spaces replace the isolation, intimidation, oppression, and help heal the harm of domestic and sexual violence.

Wendy:

My name is Wendy Schlater, and I identify as weh-potaaxaw, which means to walk with both female and male spirit/body. It took me a long time to feel human, reclaim myself, feel grounded in my skin, and really love myself! Since third grade, I knew I was different from my cousins and friends. Growing up my relatives nicknamed me Wendell and Wendoe. Reflecting on my childhood, there were hints of being weh-potaaxaw, but never a teaching or rites of passage.

Fast forward to 1993 when I came out to my Mother at 23. I remember her silence, and then asking if I had ever slept with a man or thought of having a one-night stand to make sure. I said no and I had no desire to. I remember being shocked, screaming to myself in my head and being scared. Screaming because I was frustrated she couldn’t see me… scared because my Mother was encouraging me to have sex with a stranger to prove I wasn’t weh-potaaxaw. Scared because I thought my Mother might send someone to screw me to prove I was straight. The next week my Mother apologized and told me she loved me no matter what because I was her daughter. My Mother said she was afraid, because of how she witnessed others abused who identified as LGBTQ.

“The Elders used to say there is life and power in words. I sometimes daydream that our language is floating around us waiting for us to reclaim it, to feel its power and memory of our people’s love, respect, honor, truth, openness and courage.”

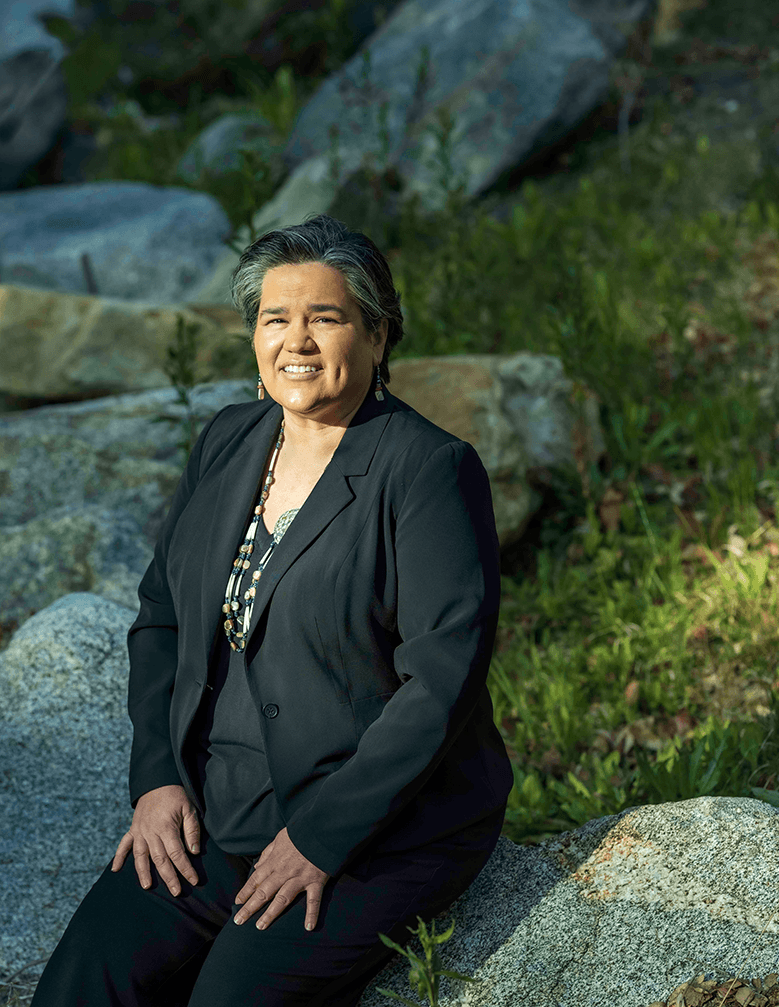

–Wendy Schlater, Vice Chairwoman, La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians

Debra:

I came out in 1978, and by the early ‘80s I was active in the lesbian gay movement in Seattle, and in the American Indian movement around fishing rights and police brutality. Back then, it was known as the gay movement. We fought for inclusion and recognition of our interconnected struggles as lesbians, feminists and people of color.

I was working closely with a Native Elder organizing a rally focused on a Native issue. We had lined up a variety of speakers to show the diverse support. I was speaking and the Elder was moderating. We had worked on several projects for 4-5 years. I had been to her home, knew her family, and looked up to her. We had a good collaborative political friendship.

It was a summer afternoon with several hundred attending. As the event organizers, the Elder and I had been working shoulder to shoulder since early morning. We were happy that the event was going really well. I spoke about the importance of all who were struggling to support one another. As we wrapped the event up, she mentioned that she was thirsty. I offered her my water that I had just taken a drink from. She did not take the bottle, and looked at me and said, “I won’t get AIDS, will I?”

I felt like I had been hit in the stomach. I was speechless, but mostly I was devastated, hurt, and shocked. I walked away, not knowing what else to do. I tried to speak to her the next day to tell her that her question had felt like she was attempting to stuff me into a gay box. I learned later that she blamed me for feeling hurt. She never spoke to me again.

Unintentional micro-aggressions can have as significant an impact as intentional violence. Once the words are spoken, they cannot be unsaid or unheard. However, there can be discussion, dialogue, apology, forgiveness, understanding, and lessons learned. Without these, there can only be hurt, mistrust and more layers added to the protective walls around self. To this day, some 35 years later, I am cautious about coming out to colleagues or friends as my protective layers have grown thick. These layers of protection and isolation can be deadly for 2SLGBTQ victims of domestic and sexual violence when they, in fact, need to be surrounded with help and support, including from family and friends.

Colorado River:

Mio ataaum wyot, ataaum Heeshatella Paayomkawichum. Nosume Nopuuliaa. (Water cloud is the ocean mist and are the tears of creator.) Since the early ‘50s, from the time I was eight to now that I am 69, I saw that our people knew that relationships between women or men to be their way and not different from anyone else. It was more natural for our people to respect LGBTQ relationships, even with changes out in the non-Indian world. It wasn’t until I joined the American Indian Movement and left my family that I realized how much the western culture influenced Indian thinking and behaviors. What I saw at home with our beliefs respecting LGBTQ relationships was the opposite with non-Indians of disrespect for LGBTQ relationships. Violence was the norm between partners. Rape was real. I told my mom not to worry about me, even after surviving too many violent acts to count, including rapes. The influence of the outside world did more harm than good, and how we survive and thrive as peoples and as 2SLGTBQ is remembering who we are as Native people. One day I will tell you more, for now I am finished.

Small waterfall along Pipe Creek River in Arizona.(Photo courtesy of Pipe Creek River.)

Wendy:

These experiences would later pin me in an abusive relationship. I had to choose between death or running to my family for help. My abuser had strangled me. I pleaded with her not to burn my face with an iron as she clutched the back of my head by my hair. The thoughts that flashed through my mind were, do or can I run, or do I fight back? Do I die? Will my family help me? I am going to die. Then I no longer noticed the heat of the iron on my face and the back of my head was free from her pulling my hair. I noticed I was alone in the room. Without a second thought, I sprinted barefoot for the door wearing a torn shirt and shorts. I looked back at the house, surprised that I had made it out alive. Then I saw a stunned face looking out the window, a face looking for its victim, for me. My gut told me to run and I did. Where am I running to? My mind replayed micro aggressions from family members like, “She’s confused?” “They are just playing house. It’s not a real relationship.” “Grow up and get a real relationship.”

I found myself at my parents’ home. I took a deep breath and walked in as if I was just there to visit. I slept that night on their couch. Morning came with breakfast and still not a word as to why I was there. I sat on the couch in my same clothes, no shoes, going nowhere fast. My younger brother asked, “What’s wrong? Why did you spend the night?” I sat there dazed and staring at him. A thousand thoughts went through my mind, including lying to protect my abuser, and fearing I would be teased with, “I told you so” to “You made your bed, now lay in it.” My other brother asked me why my neck looked dirty or bruised. My neck was sore and my voice too hoarse to lie that I had a sinus infection. I hesitated to tell the truth, not knowing how they would respond. Honestly, I was tired and drained and did not care. I was done, beaten, hurt, humiliated, embarrassed, and just wanted to move on. What happened next surprised me. My Mother and Father asked me what I wanted them to do. They offered me to stay as long as I wanted to. My brothers asked what they could do and told me it wasn’t my fault. They also offered jokingly to go beat her up…eeee…

Pipe Creek River:

I grew up on the reservation, participated in ceremonies, listened to grandmothers and many others speak our Native tongue, and I prided myself as a daughter who was a good student full of ambition. I graduated high school, moved to “the city” for college and the culture shock was overwhelming, but also exciting. I no longer had the “nosey aunties” and the “protective uncles” watching my every move. I felt finally free from judgement, the shame of acting “different” and free to act on my sexuality. I am still mostly in the closet, but my closest family and friends know that I am queer. I am not disclosing my identity due to other family members I have yet to tell.

My first queer relationship was equally incredible and devastating. She was my equal in every way–alluring, athletic, funny, smart, and amazingly witty and outgoing. As I peeled back the layers of my own shyness and insecurity, she became controlling, manipulative, and ultimately abusive. All my life, I have seen and heard story after story of domestic violence. I saw how violence hurt families, including my own, and never did I think it could exist outside a cis-het relationship.

I thought the abuse was temporary. I thought all bisexual or queer relationships had problems and I simply had to gain a footing, build trust, and establish fidelity. I thought violence only occurred in heterosexual relationships, but here I was, going from being annoyed by jealously to fearing for my life. I thought I had nowhere to go, no one to turn to who could understand my situation, and I was more fearful of my family turning me away because of my sexual orientation than fearing the purple bruised handprints on my neck.

I remember the scent of coconut as I scratched, kicked and struggled to pull her strong, beautiful hands from my neck. I remember her face, so angry, and all I could think of was my family. I remember panicking and praying, feeling and knowing this is my life leaving me. My vision blurred, and then nothing. I woke not long after, gasping for breath, and tried wailing a scream, not for help, but because I was alive and breathing and scared.

There I was, with a voice so hoarse I could barely talk, bruises on my neck, bloodshot eyes, and then the shame crept in. The shame and horror of thinking of how my family could’ve been told that my life could’ve been taken by my girlfriend. Me imagining an investigator asking my family, “You didn’t know your daughter was bisexual?” and thinking of whispers at the funeral. I curled up and refused to seek help, especially from my family.

My girlfriend stalked me for months after I ended our relationship. Her desperation to keep me felt like I was in quicksand, and I received threats at work, home, by phone, text, and then finally she threatened to out me. I then called law enforcement. Advocates tried their best to assist me, but I could not relate to the programming, nor could they grasp my needs as an Indigenous queer woman.

18 years later, I understand how colonized our concepts of gender, sexual orientation, and thinking have become. Not only did residential schools and federal policies try to destroy our culture and nations, but they changed how we view our LGBTQIA2S relatives. Settler colonialism changed how we view ourselves. I used to be ashamed of my queer identity, and now I understand that we are the diversity that our communities once celebrated and respected. I understand that my strength as an Indigenous woman doesn’t lie in being “normal” like everyone else but in being unique and beautifully queer. Indigenizing our response to our LGBTQ relatives experiencing violence will move our communities in the direction to heal from trauma. It can also help us learn healthier and practical methods of prevention that are decolonizing and intersectional. Our LGBTQ relatives need to be at the front of this movement as leaders and partners in it.

Olivia Gray and Olivia Ramirez:

I have consent from my daughter, Olivia Ramirez, to share her story in which I play a part. You can cause harm to your Two-spirit relatives in more ways than you realize, so we hope by sharing our stories to help you to avoid that. This is difficult, because just like all human beings, all 2 spirit people have their own needs, traumas, and personalities that must be navigated to avoid harm. At the end of the day, we must remember we are relatives because when we remember, then we love and care for one another.

In 2015 when my daughter was a Senior in high school, she came out to me. It was a surprise. It was not a surprise because I believed her to be straight, but rather because she was my baby and I did not think of her in terms of sexuality. In my ignorance, I also did not think of her in terms of any gender other than that which had been assigned to her at birth. I certainly did not understand gender fluidity.

We had returned to the house after dropping off one of her friends, and before I could get out of the car she said, “Hey, mom, I need to tell you something. I think you already know.” I remember being too much in my own head, thinking don’t say anything that will come out wrong like, “I love you anyway” because that implies that there is something wrong. I had all of these thoughts trying to do the right thing that I underreacted, which caused my child harm.

She told me later, “I just told you the most earth shattering thing in my life and you did not react other than to say that you needed a minute.” In my worry to do the right thing, I made it all about me and my feelings and that hurt my kid. Not my proudest moment for sure.

Her father’s reaction was quite different but no less harmful. She had been outed to her dad. She feared his reaction and the guilt that would be laid on her. His reaction sent my child walking in the dark in tears. While her sisters and I drove around looking for her, her dad called to explain that he didn’t want anyone to hurt her and I replied, “I don’t want her to hurt herself.” Since that conversation, everything has been fine.

At the end of the day, she is our child and all that matters is that she is healthy, happy, and successful (her definition of success, not ours). That is all that should ever matter with any child.

Years later, she found herself in an abusive relationship with a woman. She had talked to us about wanting to break up, but since they had moved in together, that made the breakup so much harder. My ex-husband and I devised a plan and presented it to our daughter. It worked. It was loud and ugly, but she had our love and support, and some very intimidating sisters, so she remained safe.

My ex-husband and I realized that our child was hurting and we self-corrected. We did not expect her to do that for us. It was our work to do. I believe this is why she did not stay in an abusive relationship. She knew she had her family and that we would not tolerate anyone abusing her.

Wendy:

I stayed with my parents for three weeks. My parents told my abuser she could stay in my home for three weeks, then find another place to live, not to visit any of our family homes, and not to ask for me. My family never made fun of me. They did ask why I didn’t come to them earlier. I told them I didn’t feel safe because of the way they would tease me about my relationship. They stood there in silence. Over time, we had heart-to-heart discussions.

In 2015, as Director for my tribe’s Safety for Native Women Avellaka Program which responds to violence against women, we developed our Rainbow of Truth Circle Project. We learned our language and developed material reconnecting us with our teachings defining our respectful relations with each other. These teachings are reflective of how we governed ourselves maintaining law and order and promoting healthy living long before the United States. I remember my Cousin calling me in excitement as he looked over Harrington’s notes. John Harrington was a linguist and an ethnologist who came through our people’s area documenting us in the 1930s and ‘40s. My Cousin said, “Look, this is a reference for two spirit, Weh-Potaaxaw–Weh meaning two and Po meaning he she them. Taaxaw meaning body.”

After reclaiming my people’s term, I felt grounded, visible, valued and safe, as if I had come home from living in some foreign land. The Elders used to say there is life and power in words. I sometimes daydream that our language is floating around us waiting for us to reclaim it, to feel its power and memory of our people’s love, respect, honor, truth, openness and courage. Po’eek! (That is all!)