A Native Hawaiian Call for Change

Using Native Hawaiian Culture to Address Violence Against Women

Every morning when Rosemond “Loke” Pettigrew pulls out of her driveway, she calls out to her ancestors and to her land. “Malama pono, aloha aina!” Loke says in Native Hawaiian. She is acknowledging her ancestors and telling them to “take care” at home while she is gone.

Loke lives on the ocean side of a small valley in Molokai, Hawaii. This valley is her “kupuna aina”– he land where her kupuna (ancestors) have resided since ancient times, where they worked the aina (the land), and where they lived. “When the land tenure system changed and it went from common to private, my kupuna claimed that ‘ahu puna’, that land division,” Loke explained. “So it’s kupuna because it’s the land of my kupuna, the aina kupuna.”

Loke’s sister is her only neighbor in the valley. The two sisters live with their kupuna, who are buried there, and who are still there with them. “That’s very important, always acknowledging your kupuna and those who have gone before us, because they are the ones where we come from,” Loke said. “The aina is a part of us. Without the aina, then who are we?”

Welcoming the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine to the National Movement

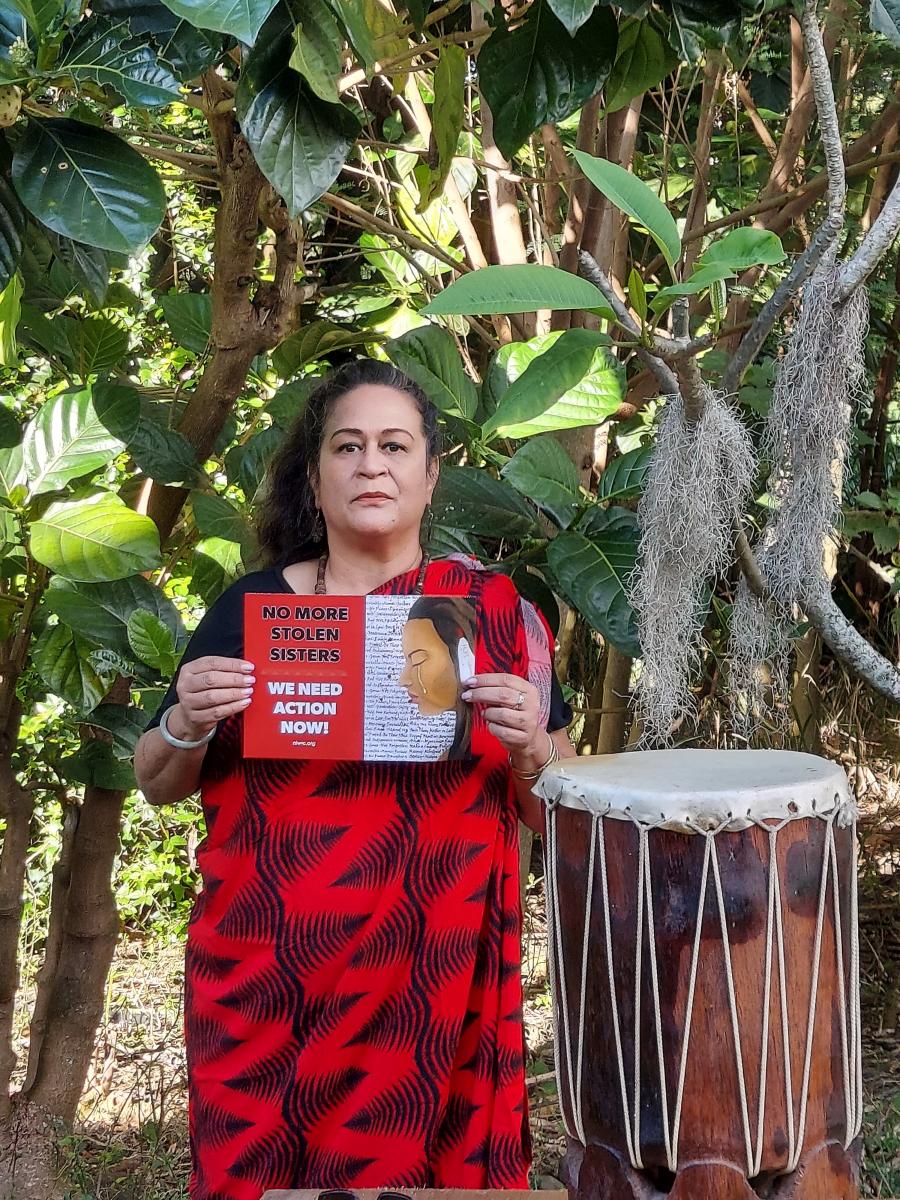

The Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine (Pillars of Women) is a grassroots collective of Native Hawaiian women advocating against domestic and sexual violence. Loke, as Board President of the organization, along with her fellow Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine sisters Dayna Schultz (Vice President), NaniFay Paglinawan, and Dolly Tatofi, use strategies based in Native culture, language, and worldview to increase the safety of Native Hawaiian women and children.

Central to Native Hawaiian culture is the relationship of everyone with one another through the land. “We’re connected through the aina because Hawaii is our home,” Loke said. But ever since the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States in 1898, the connection of Native Hawaiian people to their land has not been respected. Colonization led to the displacement of thousands of Hawaiians, resulting in increased vulnerability to trauma and oppression. Sacred land has been stolen and violated by colonizers who do not understand the importance of the kupuna aina to Native Hawaiian peoples.

Native Hawaiian women, like their land, have been subjected to alarmingly high rates of violence, trauma, and assault since colonization and into the present day. According to a 2018 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, 20.6% of Native Hawaiian women between the ages of 18 to 29 years have experienced IPV, compared with 13.3% of non-Hawaiian women, and 21% of Native Hawaiian women ages 45-59 years have experienced IPV–this rate is nearly twice as high as non-Hawaiian women (12.6%).1

The Kahea: A Call for Unity and Change

Currently, federal programming for domestic violence, such as the Violence Against Women Act and the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act, takes place in a Western context that is applied generically to all victims of gender-based violence. But the Pouhana sisters understand that “relying on these non-Indigenous responses to domestic and sexual violence are short-term, temporary solutions which do not address the needs of Native Hawaiians.”2

To raise their voices in awareness of domestic violence against Indigenous women, Loke believes Native Hawaiian women can join together using an ancient Hawaiian tradition: the kahea.

“Kahea means to call. There are several meanings. But basically for hula, when you’re ready to start dancing, you’re going to let your teacher, or your kumu, know you’re ready, so you’re going to start with a call. In addition to being used for the start of a hula dance, kaheas are also used when you arrive at someone else’s home. You’re asking for permission to be accepted. So there’s also a return call by the other. It’s calling even your ancestors to come and join you or to guide you.”

1 Office of Hawaiian Affairs. (2018). Haumea—Transforming the Health of Native Hawaiian Women and Empowering Wāhine Well-Being, https://bit.ly/3nDkxep

“If your people need healing and need to be taken care of, you have to take care of your land. If you don’t take care of your land, you can’t take care of your people.”

–Loke Pettigrew, Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine

Kaheas are used as a means to join forces and bring people together. By using it to address issues of domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking in Native Hawaiian communities, the kahea could unify Native women in a call for change.

“I believe that we can use the kahea to let survivors know to come join us,” Loke said. “And to raise our voices of awareness for domestic violence in our Native Hawaiian communities.”

One of the central demands of the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine, in coordination with the NIWRC’s national movement addressing violence against Indigenous women, is federal funding for a dedicated Native Hawaiian Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Having such a resource center would enable Native Hawaiians to develop their analysis of the barriers victims face, recommendations for legal and policy reform and social change, and culturally relevant training and technical assistance to address domestic and sexual violence in their communities.

“We need to bring awareness that this is something needed, it’s been needed for a long time,” Loke said. “Statistics are really low for Native Hawaiians because they’re lumped in with other races. We need better statistics for domestic violence, within the Native Hawaiian communities.”

Loke believes the kahea can help the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine raise awareness about the importance of funding a Native Hawaiian Resource Center. “The kahea is a means to call everyone, our elected officials, communities, organizations, and bring everyone together to start really looking at this issue and how we can each make a difference in the lives of our women and children for the future benefit.”

How to Heal

In essence, the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine exists for one crucial reason: to heal their communities from trauma caused by colonization and the related effects on domestic and sexual violence. And for Native Hawaiians, healing is a process that is intimately tied to their kupuna aina, the land where they as a people have resided for generations.

“The life of the land is in its people,” Loke said, quoting the Native Hawaiian writer Dana Naone Hall. “If your people need healing and need to be taken care of, you have to take care of your land. If you don’t take care of your land, you can’t take care of your people.”

This process of healing is all part of the Native Hawaiian concept of ho’oponopono, which means to make things right. “The abuse has been carrying on through at least four generations, and it’s going to take a lot of work. Because you have the next generation of 30 and 40-year-olds that are still oppressed, emotionally, maybe in other ways as well, with the violence in their families. And if it’s there, then it’s carrying on to the next generation.”

“You need to regain who you are and where you come from to heal,” she added. “Connecting and accepting who you are and where you came from is important for healing, because you’re not only healing your present self, but you’re healing your past self. You’re healing your kupuna who have suffered as a result of just being Indigenous or Native Hawaiian, by government oppression, even oppression by your own people in some cases. It’s a generational thing. So you have to go back to who you are, where you came from, and identify your family, and address it.”

In this way, the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine are healing more than just the trauma of current-day survivors–they are healing the pain that Native Hawaiians have endured since the 1800s when colonization began. This healing process is uniquely Hawaiian, addressing domestic and sexual violence in a way that empowers survivors to reclaim their identities through Native Hawaiian culture.

The sisters of the Pouhana ‘O Na Wahine understand that for Native Hawaiian women, true healing can only occur when a woman’s identity–her family, land, ancestors, culture, and history –is fully embraced as part of herself. In Loke’s words, “When you connect to your family, or your ohana, and you start to know who you are and what your place is as an Indigenous woman, then you can see that this is who I am, and this is who I’m proud to be.”