Violence Against Indigenous Women Migrating to the United States

(Left to right) Dr. Cintli (Macehual, Mexico) and Antonio Ramirez (Diné) at the 2019 Maya Maiz Roots Conference prayer run in Tucson, Arizona to honor missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW) victims, including Claudia Patricia Gomez. (Photo courtesy of Indian Law Resource Center.)

Violence against Indigenous women is a global crisis that takes many forms and is further intensified when women are forced into migration. And while it is crucially important to focus on crimes committed against individuals by specific perpetrators, we must also understand that this violence is rooted in the systems of discrimination and exploitation that colonialism established in our territories. Colonialism seeks to undermine our traditional forms of governance in order to make it easier to seize our lands and resources, sending Indigenous peoples into exile or poverty. Colonialism uses various forms of violence against women to further weaken our nations, justifies this violence by dehumanizing Indigenous peoples, and then denies us the human rights that non-Indigenous people enjoy.

In the United States, we see this happen when Indigenous women on Indigenous lands are assaulted by non-Indigenous perpetrators, and our Tribal governments are prohibited by law from responding to these crimes unless our Tribes meet the stringent requirements in VAWA. This discriminatory legal structure leaves Indigenous women less protected than all other women in the United States and, in many cases, completely unprotected. It denies our Tribal governments’ sovereign authority over our territories, and allows perpetrators to commit crimes with impunity, as if Indigenous women were not humans with rights protected by U.S. and international law.

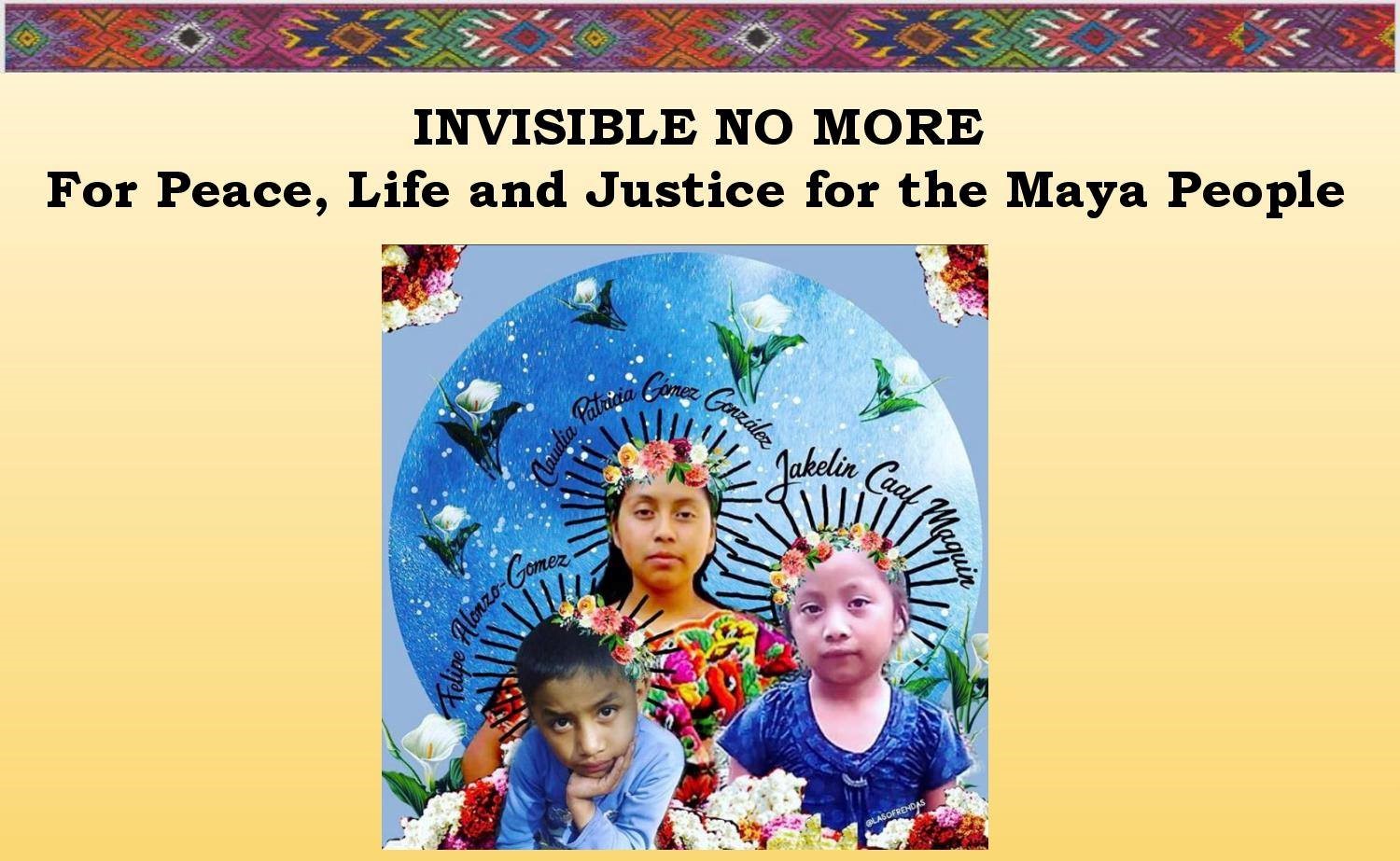

This same violence takes many different forms under today’s realities where Indigenous women, particularly those living in Mexico, Central and South America are forced into migration due to human rights abuses and desperate economic pressures at home. On May 23, 2018 in Rio Bravo, Texas, a United States Border Patrol agent shot Claudia Patricia Gómez González in the head and killed her. Claudia Patricia was a 20-year old Indigenous woman. She was Maya Mam, from San Juan Ostuncalco, Quetzaltenango in Guatemala. Her tragic death exemplifies the overlapping forms of violence Indigenous women in the Americas face. Claudia lived in poverty in a village in the highlands of Guatemala. According to Juanita Cabrera Lopez, Executive Director of the International Mayan League, “Guatemala still perpetuates human rights violations, systemic oppression and exclusion of indigenous peoples at all levels of society. There are debilitating inequalities in land ownership, control, and management. The forced migration of my people from Guatemala is a symptom of the underlying causes derived from not only decades but from over 500 years of land theft, oppression, racism, and institutionalized exclusion of the predominant indigenous peoples. For indigenous girls and women, the exclusion and racism is worse.”

To escape this poverty, lack of opportunity, and violence in her home country, Claudia Patricia was forced to migrate to the United States. While migration itself is very dangerous, Indigenous migrants face particular obstacles due to the intersection of identity, gender, racism, and language. This places them at extremely high risk of being trafficked or sexually assaulted during their journey, and because of Indigenous language exclusion, often leaves them unable to seek help. Despite these obstacles, Claudia Patricia arrived in the United States. And then, apparently within minutes of her arrival, she was shot to death by the U.S. Border Patrol. And then nothing happened.

Three years after Claudia Patricia’s death, there have been no prosecutions. A civil suit against the officer alleged to be responsible for her death is paused while the FBI investigates. In 2019, on the first anniversary of her death, Claudia’s father said, “These days have been so difficult, so many people have been calling me, asking what is our message? What do we want people to know? We are tired. There comes a point when I just don’t know what to say anymore. As more time goes by, it is more difficult for us, we miss her so much. But what I ask is that there is justice for her. This is what I have always asked, JUSTICE. We want answers.”

It is this search for justice, in all of its forms, that is behind so much of the work that we do. Whether we are working to reform federal law or change the policies at our local police department; to run a shelter, or, like Claudia Patricia’s father, to fight the terrifying culture of silence and impunity that is behind the MMIW crisis, what we are seeking is justice. We seek justice for our sisters who experience violence so that we can understand what happened and why. We seek justice against the perpetrators of these crimes so that future acts of violence can be prevented, and so that wrongdoing can be publicly denounced. We seek justice for our Tribes and nations so that we can build communities that can protect our families by protecting all of our human rights.

For more information about the human rights situation of Indigenous migrants to the United States, contact the International Mayan League (Mayan League) or visit their website at www.mayanleague.org. The Mayan League is a grassroots, Indigenous women-led Maya organization founded in 1991 by Maya refugee men and women with allies from the Sanctuary Movement.

Their work and priorities are guided by the vision and practices of their spiritual and traditional leaders, elders, and authorities. They work to promote, preserve, and transmit the culture and contributions of the Maya to create solutions against current threats and violations affecting Indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica and the United States. The Mayan League works to address the immigration crisis at the border and throughout the U.S., and Indigenous peoples’ human rights.

As part of this work, the Mayan League led the advocacy effort to secure a National Congress of American Indians Resolution, “Calling to Protect and Advance the Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples Migrating to the U.S.” In this resolution, NCAI called upon the U.S. Departments of Homeland Security and Justice to “conduct an independent, exhaustive, and transparent investigation concerning the deaths of all Indigenous children in U.S. custody and by U.S. Border Patrol employees at the southern border, and hold all those responsible accountable for the deaths.” The full text of this resolution is available at https://bit.ly/3yFJmtM.

Currently, some 281 million people, or about 3.6% of the world’s population are living outside their country of origin. In July 2021, the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution on the human rights of migrants, available at https://bit.ly/3mUJPWM. Among other things, the resolution recognizes that migrants are human rights holders whose rights to safety and dignity must be protected and respected, that each State may determine its own national migration policy within its jurisdiction consistent with its obligations under international law, and that States are responsible for protecting the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all migrants present in their territory and subject to their jurisdiction. The resolution also expresses deep concern for the growing numbers of migrants who have lost their lives or gone missing while attempting to cross international borders and calls on the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to convene a one-day panel discussion on the human rights of migrants with a summary report to the Human Rights Council at its 50th session. For additional information about the violation of the human rights of migrants at international borders, visit the UN Office of the High Commissioners migrants webpage at https://bit.ly/2WLa1YN.