Safe Housing: The Need for Shelters for Native Women Who are Battered

By Brenda Hill (Siksika), Director of Technical Assistance and Training, NIWRC

The home, who leaves when domestic violence occurs? In discussions about the importance of safe shelter and advocacy services the assumption often is that a woman who is battered must be the one to escape, find shelter, and then permanent housing. Let us stop for a moment and ask ourselves a question about this western assumption now common across Indian tribes. Why do we as advocates and as a social justice movement find it acceptable that women who are victims of serial violence are expected to leave their homes?

Our movement for the safety for Native women began with our belief of women as sacred and that as relatives we are responsible for each other. This belief was indigenous to tribal peoples as a way of life. Our movement began with the purpose of making women safe, including in their own homes, and the original protections of our tribal beliefs offers a strong foundation to continue to guide our movement.

I remember a woman with this belief saying, ‘I’m not leaving. I pay for this house. I bought everything in it. Why is everybody telling me I have to leave my own home? And then you tell me I’m a victim, and then you tell me it’s not my fault, but I’m the one who’s got to go.’ A few months later her position changed. ‘I give up. I left. I left my own home. I had to leave all my stuff. Are you sure I’m the victim? I have to give up everything—what about him?’

In our conversations about shelter and advocacy we need to challenge the assumption that survivors of violence must escape from their own home. We also need to understand why this is the assumption of the western justice system. Why it is also the assumption of the range of service providers? Too often advocates also work under this assumption.

Why is it too dangerous for survivors to stay within their own home? Is it because the United States is not upholding the federal trust responsibility to support Indian tribes in safeguarding the lives of Indian women? Native women are forced to flee their homes and often homelands due to federal law and policies that leave them unprotected and vulnerable. The lack of sufficient appropriations to Indian tribes to support adequate law enforcement, batterer’s reeducation, a health response, and safe housing are just some examples of the consequences of a failed federal system. It’s important to question why, as Native people, we struggle to provide safety for victims and offender accountability. The end result of this failed system is put on the backs of the victims. The survivors are forced to find their way through it all.

If we believe women are sacred, then shelter is a place to nurture that sacredness. We need to do this together as women. And then it’s about taking action.

Accountability for Abusers so Victims Are Not Forced to Become Homeless

A man who had himself been arrested for domestic violence asked me why victims are forced to hide out. He started out saying, “I know a lot of guys who are batterers. And after thinking about it I came up with a huge list of men that I know are battering their wives and that weren’t arrested. And this is huge issue. I want to know why there is not some shelter for them.” And his point was that you’re making these women and their kids hide out in a shelter and they can’t go freely about their lives, but these guys are. “Why aren’t the guys put in some kind of shelter where they can’t move around freely.” He understood forcing women and their children to leave their home is wrong. While I would not call it shelter, appropriate jail time, extended, intensive probation, and court ordered long-term, culturally-based batterers reeducation is appropriate – though funding and housing are, again, major issues.

A Continuum of Services for Women Who are Battered to Heal

Before colonization the tribe or family of a man who hurt a woman would be so shamed, they took responsibility for making sure she was safe. But in modern times, this has changed. Today shelters are integral to women’s safety, yet women also need a continuum of services based on the complexities of reclaiming one’s life. It is inhuman to require someone traumatized to deal with safety, courts, child custody, housing and so many other all at the same time. It’s like requiring someone who has been repeatedly hit by a truck, to get up and carry on with life. Women need some place to rest and heal. It is a necessity.

Traditionally there was an understanding that you don’t heal alone. Women have a need to come together. There is healing in coming together. It is about relationships and we need each other to get through the difficulties, all the challenges. Anyone who has been battered will probably say it was being able to talk to other women that have been through it, that helped them understand their own experience and be able to heal from it. That is the origin of advocacy.

Women are in danger because the offender has not been stopped and held accountable.

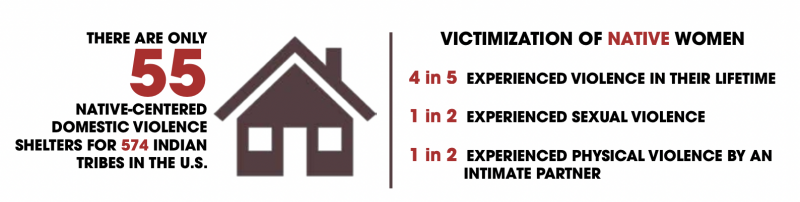

In the early 2000s, Sacred Circle National Resource Center reported 26 Native shelters, and currently there are approximately 55 shelters for Native women. Just thirty Native shelters were added over the last twenty years. Why only twenty? The number of Native shelters is connected to the lack of adequate federal funding. It is also connected to the lack of tribal infrastructure including staff to apply for grant funds to create and maintain a shelter. Some tribes have staff to write grants while many do not. Tribes just do not have the staff to write the applications to access the funding for a shelter. A third issue is finding staff, either survivors, or survivors of a close relative that understand the need for the shelter program and has the wherewithal to pull it together. In small villages for example the amount of money it takes to run a shelter is expensive and difficult. And in many tribes, it goes back to having a building available for a shelter. It is also a question of the number of survivors needing services or shelter. It may not be realistic. In these tribal communities a consortium may be the approach to take.

The funding under the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) has been the anchor for tribal shelter programs for decades. As the only federal program dedicated to shelter and related services it has made a real difference. Shelter and program directors love FVPSA because it is flexible enough for real women’s (and their children’s) needs. This flexible funding is needed because each tribe is different and the healing journey for Native women varies. A Native woman in a Yup’ik speaking village in Alaska has beliefs and traditions specific to her tribal nation that are distinct from a Lakota woman. While the funding under FVPSA was never adequate, because it is flexible it addresses the needs of tribal women and other survivors, more than other federal programs. When you looked at advocates on the ground, the women needing services, there’s just simply not enough funding. We can provide all the technical assistance in the world, but for a program without sufficient funding, it does not matter.

Indian tribes have advocated for amendments to FVPSA that are included in its 2019 reauthorization. These tribal amendments were all included in the pending bills except for the amendment that would increase funding to Indian tribes to provide shelter and services to women. Given a shelter or advocacy can mean the difference between life or death for a Native woman FVPSA must be a priority. Congress should fulfill its federal trust responsibility and include the increased funding for the tribes.