Exercising Sovereignty to Respect and Protect Native Women

Reflections from Pascua Yaqui and Muscogee (Creek) Nations

Kathryn Nagle (center) at the October 2022 NCAI VAW Task Force.

Photo courtesy of Paula Julian, NIWRC.

Years ago, an advocate who spoke English as a second language to her Native tongue asked what sovereignty is. I said sovereignty is how Indigenous peoples live daily according to their Tribal specific customs and traditions.

So exercising sovereignty means living day to day according to your Tribal specific customs and traditions. Exercising sovereignty to respect and “protect” women recognizes that how Indigenous Nations have governed their Nations means that all women are respected in thoughts and behaviors, and abusive thoughts and actions result in immediate consequences. Over the past 27 years, since the passage of the first Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), Indian Tribes have exercised their sovereignty and upheld their laws, customs, and traditions respecting and protecting women. With each reauthorization of VAWA, Tribes have addressed the barriers created by federal and state governments resulting in disproportionate rates of violence against American Indian and Alaska Native women. We share the inspiring reflections below from two Tribal Attorney Generals who help their Tribes exercise sovereignty each day toward this end. They provided an update at the October 2022 National Congress of American Indians Violence Against Women Task Force Meeting. We thank all Tribes for respecting and protecting women and advocating with the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center and many other Tribal and Native Hawaiian organizations and allies for women’s safety.

Alfred Urbina spoke on the implications of the Castro-Huerta ruling and a program created in partnership with Arizona’s Pima County Attorney.

“We were one of the first pilot Tribes (to implement VAWA 2013), and we’ve been prosecuting non-Indian offenders for about nine years. We’ve had at least 115 cases. It’s almost become routine. So, this new case out of Oklahoma (referring to Castro-Huerta) – “Okay, at Pascua Yaqui, now the State can handle these cases too.” So, that’s a problem for us because we’ve been prosecuting those cases. We know our community. Our law enforcement officers are state certified. They respond to the calls, and they go into our Tribal court. We know the victims. The victims live on the Reservation in Tribal housing. So, to have another jurisdiction, and the Supreme Court say that the State can come in here and prosecute these cases also could cause many problems. We have a good relationship with our state and federal counterparts, the US Attorney’s office, and law enforcement around the Reservation. And so we thought, “how do we address this?” Right after we started prosecuting non-Indian offenders who live off Reservation, we were already thinking, “how do we monitor them if they live off Reservation?” We thought about an agreement with the state. We modified the agreement to clarify that the County attorney would appoint a Tribal prosecutor as a special deputy county attorney. This Tribal prosecutor will bring cases into state court that arise from the Reservation. Cases could be anything, including a non-Indian who had their purse stolen in our casinos by a non-Indian person. Our law enforcement officers, who are state certified, can arrest and book that person into the county jail. We’ll be able to help prosecute those matters in state court. Essentially, that gives us the ability to manage or control what’s happening on the Reservation. It’s the further development of our crime-control policy.

So, if we can investigate all cases and bring these cases in any jurisdiction (Tribal, state, or federal), then we’re essentially addressing all the gaps we have historically seen in Indian Country. And there’s accountability because we know who investigates and who will prosecute. We can always go to those two entities the Tribe has control over and ask them about what’s going on in each case. Everything is local; everything is here. It makes sense when you consider who patrols your neighborhood and who is responsible for those things. Most of those things we take for granted—when we call the cops, someone will come and be arrested if someone does something criminal. We don’t have a second thought about it; we just call 911. That’s what we’re trying to have happen here, that’s justice. We should have that same level of comfort and safety that someone in Tucson, Phoenix, or Flagstaff has.”

Geri Wisner discussed issues surrounding sentencing limitations as well as the resiliency found among the Muscogee-Creek Nation.

“I let (victims) know that I am aggressive, and I fight because I want justice for them. But the reality is that on a homicide or a rape case, my maximum sentence is one year and/or a $5,000 fine. Or if it were a Tribe that followed and implemented the Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) sentence enhancement, the maximum criminal sentence is three years and/or $15,000...I believe, and I’m, unfortunately, starting to see, that limited sentencing puts a target of vulnerability on our Tribal members’ backs. Almost as if, “If you hurt a Native, then it’s only three years,” versus anywhere else, anyone else would get a significantly harsher sentence. So my point is this: the charging and sentencing limitations put upon Indians from either the (Indian) Civil Rights Act, from Oliphant, or from all of the racist ideals and lenses that non-Natives use to look at Tribal justice have to be removed. Otherwise, we’re making our people vulnerable. And we have some of the brightest minds as Native prosecutors, judges, and defense attorneys. We have very intelligent, educated, and dedicated people working toward justice in Indian Country, but we need to be able to recognize and implement their recommendations. We need the sentencing limitations of three years for violent crimes removed so that we can aptly and appropriately sentence crime as we see fit. We should be able to fully open the door and prosecute all crimes committed within the Reservations.

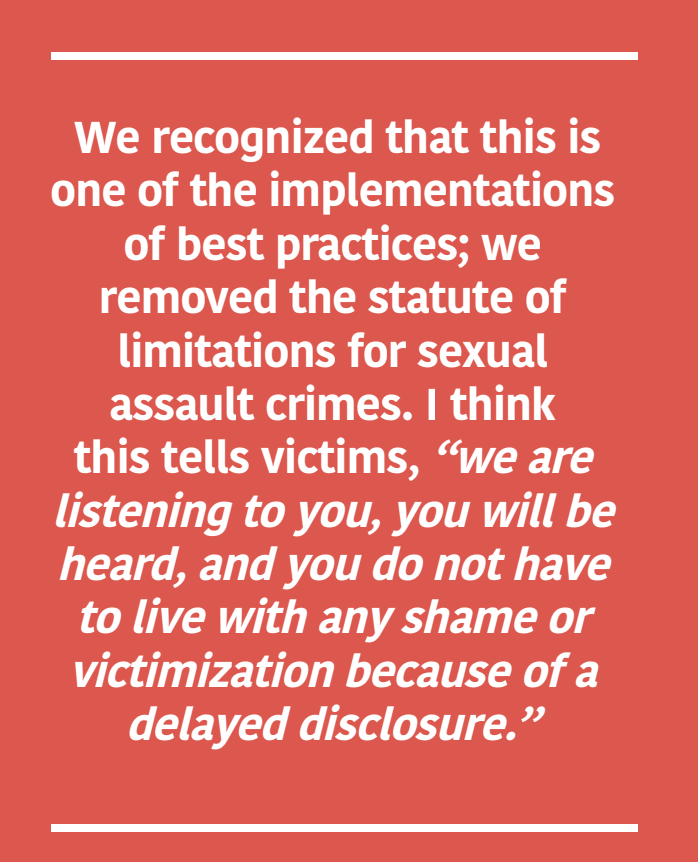

The National Council of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had recently (two months before the NCAI Task Force meeting in October) signed the resolution recognizing the VAWA 2022 expansion. In addition, we passed our updated Tribal Criminal code, which gave us an opportunity to look at our laws. We recognized that this is one of the implementations of best practices; we removed the statute of limitations for sexual assault crimes. I think this tells victims “that we are listening to you, you will be heard, and you do not have to live with any shame or victimization because of a delayed disclosure.” If it is beyond seven years, tell me what happened. I will try to prosecute it. We listen. We don’t cut off anyone mid-story if we find out it was eight or ten years ago. We will prosecute those cases because I think jurisdictions are listening to the research, that delayed disclosures are the norm, and we recognize a multitude of reasons why there is a hesitancy to report sexual assault. Our justice systems need to be more cognizant of the research that has been coming down for a long time. And so, this is an example of a best practice that I’m excited to see in use.

We have so much work to do to help victims and our people heal. But we are resilient, strong, and we have our healing songs, so let’s sing. Let’s sing our healing songs to our babies, sing to our elders and families, and get ourselves healthy and strong.”

between the Pascua Yaqui Indian Tribe and Pima County.

Photo courtesy of Alfred Urbina.

Alfred Urbina and Geri Wisner are helping their Tribal nations create more culturally centered, safer, and resilient communities with their dedicated heart work. They are strengthening their Tribal court system unique to their Tribe by exercising their respective Nation’s sovereignty. A common thread among their interviews was the importance placed on culture and understanding what safety in the community means to them. The western colonized version of a successful justice system does not translate within Tribal communities. More jails are not a measure of safety. Rather, these Attorney Generals place value in safety through a victim’s perspective. Appropriate accountability for perpetrators, protection of women and children, and investment in community health from an Indigenous perspective are the pathways to a stronger, healthier Tribal community.