Land Threats

Women and Mother Earth are Sacred

Women and Mother Earth are Sacred

Indigenous peoples across the world have continuously been at the forefront of resistance to extractive industries, which place corporate interests above the well-being of our planet and the life it sustains. In the United States, extractive industries have displaced, destroyed, and irreversibly damaged sacred land for centuries, and continue to do so. This destruction marks the clear continuation of colonization, as Indigenous peoples across the world are forced out of their ancestral lands, and face cultural genocide and violence as an effect of extractive industries.

“Not only do extractive industries have a negative impact on the environment––the air, land, water, cultural practices––that Tribes depend on, they also negatively impact Native women and girls by subjecting them to increased levels of violence.”––Kerri Colfer, Tlingit, Senior Native Affairs Advisor, NIWRC.

In many Indigenous perspectives, waterways, Mother Earth, and women are all viewed as life-givers and are therefore interrelated. Indigenous peoples across various communities and cultures recognize the connection between women and land––and hold both as sacred. Colonization, however, is built upon the violent belief that land and bodies are resources––something to own and consume. This philosophy allowed government-sanctioned violence against Indigenous communities, where the dehumanization, rape, and murder of Indigenous women were permitted as an extension of colonization. Colonizers imposed patriarchal systems upon Indigenous communities and eroded Indigenous systems of governance that hold women and Mother Earth as sacred.

This erosion of sovereignty has led to the loss of Indigenous life-ways, customs, and laws that safeguard Indigenous women and the environment from acts of violence. While Indigenous people recognize that the land and women are connected, and therefore any act of violence against the land is an act of violence against Tribal communities, there is a clear and documented connection between extractive industries and violence against Indigenous women.1

As corporations construct pipelines and mines for profit, often within or bordering Tribal lands, they develop “man camps” or temporary settlements of transient workers proximate to these extractive projects. These “man camps” cultivate a culture of misogyny, drug abuse, and racism.2 This culture is bolstered and made deadly by the anonymity of these workers––who are mostly non-Indigenous, white males––within Indigenous communities, and the social, political, and judicial structures that demonstrate to these transient workers that they can commit crimes within Native Nations with relative impunity. This lethal mixture of sociopolitical factors facilitates the rise in trafficking, murder, sexual assault, and other violent crimes against Indigenous women surrounding these extractive developments.3

An interactive map highlighting more extractive industry resistance is available below. If you have additional land threats or more information, please fill out this form.

Reclaiming Indigenous matrilineal beliefs and restoring sovereignty to Native Nations and Indigenous people across the world is therefore central to protecting Indigenous women and holding extractive industries accountable. Indigenous resistance to the destruction of Mother Earth comes in innumerable forms, most of which go unnoticed by mainstream media. More recently, there has been more recognition of the crucial role Indigenous people undertake and continue to hold in the environmental movement. However, these movements must be lifted, heard, and understood on a much larger scale to combat the further destruction of our planet.

This article highlights five Indigenous-led movements fighting to defend land and women against extractive industries across Turtle Island and includes links to learn more and take action. The movements noted here are only a fraction of those happening.

View map

The United Tribes of Bristol Bay (UTBB) | Pebble Mine | Alaska

Learn more: utbb.org

Take action: Join the UTBB in calling on the EPA to finalize permanent protections for Bristol Bay: utbb.org/public-comment

In 2001, a Canadian company, Northern Dynasty, acquired state leases to begin constructing the Pebble Mine––a deposit with copper-, gold-, and molybdenum-bearing minerals––located on Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq lands, known as Bristol Bay, in southwestern Alaska. Bristol Bay contains 40,000 square miles of wild tundra, pristine streams, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and headwaters that have provided sustenance to Alaska Natives for centuries.4

Most notably, the Pebble Mine is located just 100 miles away from headwaters of two major rivers that flow into Bristol Bay, the Kvichak and Nushagak, which are essential for the well-being of Bristol Bay’s salmon population, a central part of the cultural practices and physical health of the 31 federally recognized Tribes in the region.5

Alaska Natives immediately began opposing this mine. In 2007, the Alaska Native Village Corporations formed Nunamta Alukestai, the first regional opposition to the Pebble Mine. In 2013, the United Tribes of Bristol Bay, a consortium of 15 Tribes, representing over 80% of the region’s population, formed. Since its inception, UTBB has been working alongside fishing and environmental partners to maintain resistance to the construction of the mine and push the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to take action.

In 2014, an EPA Assessment that confirmed the environmental impacts the Pebble Mine would have on the pristine waterways of Bristol Bay6 sparked a yearslong lawsuit filed by Northern Dynasty. In 2017, the case was settled, its scientific findings confirmed, and ultimately in 2020, the Army Corps of Engineers denied the company’s permit.7

United Tribes of Bristol Bay and its partners released a “Call to Protect Bristol Bay” in December 2020, which calls on the EPA to enact 404(c) Clean Water Act (CWA) and establish a National Fisheries area to provide long-lasting federal protection and permanently ban toxic mine waste from irreversibly contaminating Bristol Bay. The EPA has yet to decide whether to enact the 404(c) CWA and pushed its timeline to May 31, 2022.8

Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes | Thacker Pass, Peehee Mu’huh | Nevada

Learn more: peopleofredmountain.com

Take action: Pressure lawmakers to protect Thacker Pass: protectthackerpass.org/build-pressure.

Twenty-five miles south of the Fort McDermitt Reservation in northern Nevada is a desert landscape filled with old-growth sagebrush and chokecherries called Peehee Mu’huh or “rotten moon” in Paiute and federally recognized as “Thacker Pass.” For Daranda Hinkey (pictured above), one of the founding members of Atsa Koodakuh why Nuwu (People of Red Mountain), this land is made sacred by the bones of her ancestors who rest beneath the soil.9 Currently, this sacred land is in the process of being turned into the United States’ largest lithium mine by Lithium Nevada Corporation.

In late 2019, and into 2020, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) went through the process of permitting, and formally approved the mine in January 2021. People of Red Mountain, led by Hinkey, gathered at Thacker Pass to collect traditional medicine, conduct ceremonies, and protest the mine. In July 2021, the People of Red Mountain and Reno-Sparks Indian Colony filed a federal lawsuit arguing that BLM ignored crucial environmental impacts and did not adequately consult Tribes, therefore violating the National Historic Preservation Act. In December 2021, the Tribes added more claims to the suit after more evidence was unearthed through a Freedom of Information Act that BLM ignored Tribal leaders’ concerns regarding the cultural significance of Thacker Pass.10

Lone Pine Paiute-Shoshone and Timbisha Shoshone Tribes | Conglomerate Mesa | California

Learn more: Visit protectconglomeratemesa.com or join the mailing list for updates.

Take action: Sign the petition.

Conglomerate Mesa is nestled between the Timbisha Shoshone and Paiute Shoshone traditional homelands, on the edge of what is commonly known as Death Valley National Park. Tribes in the area walked this land for centuries: gathering pinyon nuts, hunting mule deer, burying their ancestors, and performing ceremonies.11 K2 Gold, a Canadian company, is seeking a permit from the BLM to create an open-pit cyanide gold mine on these sacred lands.

Both the Lone Pine Paiute-Shoshone Tribe and the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe formally expressed their opposition to this project, and called on the government to reform the 1872 mining law, which many argue, places the interests of extractive industries over social, cultural, and environmental concerns.12 The Tribes joined a coalition of organizations opposing the mine called the Conglomerate Mesa Coalition, and the BLM is still in the process of reviewing public comments and producing an environmental assessment.

Apache Stronghold | Oak Flat, Chi’chil Biłdagoteel | Arizona

Learn more: Follow updates from Apache Stronghold at apache-stronghold.org

Take action: Urge Senators to save Oak Flat.

Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, now known as Oak Flat, part of the Tonto National Forest in Arizona, is a center of identity and culture for over 10 Tribes in Arizona.13 It is a place of sacred connection between the physical world and Creator, where many ceremonies must take place, such as the Sunrise Ceremony, Holy Ground ceremonies, and sweat lodge ceremonies.14 (Read more in the June 2021 issue of Restoration.)

In March 2021, the U.S. federal government rescinded a final environmental impact statement that would have paved the final road for the transfer of 2,000 acres of federal land, including Oak Flat, to Resolution Copper to create a 950-foot-deep sinkhole to mine for copper.15

The Apache Stronghold filed a lawsuit and an emergency injunction to block the land swap, citing violations of the 1852 Treaty of Santa Fe and violations of their freedom of religion. The case was heard in the ninth circuit Court of Appeals on October 22, 2021, (Apache Stronghold v. United States of America).16 The Judges have yet to issue a decision.17 If the court sides with the U.S. Forest Service and confirms the land transfer of Oak Flat, Apache Stronghold could take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In May 2021, a House committee approved Save Oak Flat, a bill that would stop the land transfer. However, it has since stalled in Congress. In December 2021, a group of San Carlos Apache elders and students organized at U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly’s office in Phoenix, urging him to push forward lasting protections for Oak Flat.18

Bay Mills Indian Community | Straits of Mackinac, Great Lakes | Michigan

Learn more: Stay updated and learn more about Bay Mills Indian Community’s case.

Take action: Visit NARF’s page to stay updated on any calls to action led by the Bay Mills Indian community at narf.org/bay-mills-line5-pipeline

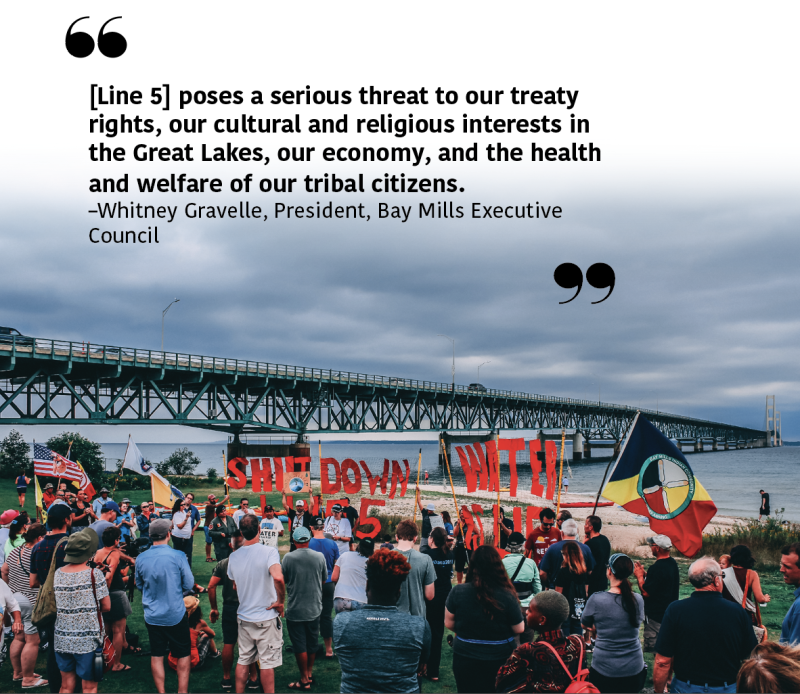

The Anishinaabe people of the Bay Mills Indian Community recognize the Straits of Mackinac, where Lake Huron and Lake Erie converge, as the center of creation. Since time immemorial, the lifeways of the Anishinaabe people have been tied to the Great Lakes and the Straits of Mackinac. Traditional fishing knowledge is passed from generation to generation, and fish are used in traditional naming and other ceremonies.19 The Straits are not only culturally interconnected with the Tribe, but the water provides sustenance and economic survival to Bay Mills Tribal members through its vital fish population.20

Enbridge’s Line 5 currently runs crude oil through the Straits of Mackinac—a project approved by the State of Michigan in the 1950s that violates treaty rights. According to President Whitney Gravelle of the Bay Mills Executive Council, the pipeline “poses a serious threat to our treaty rights, our cultural and religious interests in the Great Lakes, our economy, and the health and welfare of our tribal citizens.”21 It is also important to note that Enbridge workers have been linked to sex trafficking along the Line 3 route in Minnesota.22

In 2020, Bay Mills Indian Community teamed up with the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and Earthjustice to file a suit against the Michigan Public Service Commission (MPSC) in opposition to Enbridge’s proposal to rebuild a new massive tunnel, becoming the first Tribe to contest a proceeding before the Commission. This process is ongoing.23

In May 2021, The Tribe voted to banish the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline from the Reservation to protect Tribal citizens, the water, and all the life it sustains from the risk of an oil spill. Around the same time, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer issued a shutdown order to stop operating the Line 5 pipeline. Enbridge continues to operate Line 5 illegally.24

Photo courtesy of Whitney Gravelle.

[1] Blood and Land Memory: Land Acknowledgement and Honoring Indigenous Peoples

[2] Examples, Amnesty International’s Out of Sight, Out of Mind report on energy development and violence against Indigenous women in Canada, or the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (Canada) Final Report.

[3] Wet’suwet’en Isn’t Just About a Pipeline, but Keeping Indigenous Women Safe

[4] Drilling Down: An Examination of the Boom-Crime Relationship in Resource-Based Boom Counties” Western Criminology Review 15(1):3-17 (http://wcr.sonoma.edu/v15n1/Ruddell.pdf).

[5] Alaska Natives Lead a Unified Resistance to the Pebble Mine

[6] Pebble is over 100 miles from Bristol Bay

[7] Proposed Determination of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10 Pursuant to Section 404(c) of the Clean Water Act Pebble Deposit Area, Southwest Alaska

[8] A Brief History of Pebble Mine — United Tribes of Bristol Bay

[9] EPA Announces Next Steps in Process to Protect Bristol Bay Watershed Under Clean Water Act Authority | US EPA

[10] Public Comment Period opens for controversial mining project on California desert tribal lands - Indian Country Today

[11] Testimony of Kathy Bancroft | Walking Water, or A corporation wants to mine for gold near Death Valley. Native tribes are fighting it | LA Times

[12] Native opposition to Nevada lithium mine grows | Grist

[13] PRESS RELEASE: New Legal Claims Filed Against Thacker Pass Lithium Mine | Protect Thacker Pass

[14] https://bit.ly/3t6WIwo

[15] https://bit.ly/3t6WIwo

[16] https://bit.ly/3nERLdk (p.13)

[17] Apache Stronghold v. United States - Becket

[18]Apaches Ask Appeals Court to Oppose Transfer of Arizona Land

[19] Apache Stronghold delivers message to Sen. Mark Kelly: Save Oak Flat

[20] President Whitney B. Gravelle’s Direct Testimony

[21] Enbridge’s Line 5 Pipeline - Native American Rights Fund | Native American Rights Fund

[22]President Whitney B. Gravelle’s Direct Testimony

[23] Line 5 Pipeline | Earthjustice

[24] Experts Sound Alarm On Line 5 Oil Pipeline Tunnel Climate Impacts - Native American Rights Fund

[25] Sexual violence along pipeline route follows Indigenous women’s warnings | Minnesota | The Guardian