Special Law Enforcement Commissions: Increasing Options in Indian Country

Country Training Coordinator,

US DOJ. / Photo courtesy of

Leslie A. Hagen.

One challenge in investigating cases in Tribal communities is the limited number of law enforcement personnel and frequent turnover in Tribal police department staffing. Getting Tribal and local law enforcement officers a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), Office of Justice Services (OJS) issued Special Law Enforcement Commission (SLEC) is one way to get additional “boots on the ground” able to exercise federal authority for crimes committed in Indian country. An SLEC allows officers to enforce federal criminal statutes and federal hunting and fishing regulations in Indian country.

OJS issues SLECs to Tribal, Federal, State, and local full-time certified law enforcement officers who will serve without compensation from the Federal government. Authority to enter into Deputation Agreements and SLECs is based on federal law and federal regulations.1

As stated in Section 4-04 of the BIA-Office of Justice Services Law Enforcement Handbook 3rd Edition, SLECs are to be issued or renewed at BIA-OJS discretion and only for legitimate law enforcement needs.2

Officers seeking an SLEC must meet certain minimum qualifications. In part, these requirements include:

- The officer must be a full-time certified law enforcement officer of a Federal, State, local, or Tribal law enforcement agency.

- The officer must not have been convicted of a misdemeanor offense the year preceding the issuance of the SLEC, except for minor traffic offenses, excluding misdemeanor DUI/DWI convictions.

- The officer must never have been convicted of a misdemeanor crime involving moral turpitude (including any convictions expunged from the applicant’s record).

- The officer must never have been convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic abuse that prevents the applicant from possessing a firearm or ammunition.

- The officer must sign a “Domestic Violence Waiver” certifying that they have never been convicted of a domestic violence offense, including convictions in a Tribal court.

- The officer must have successfully passed the Criminal Jurisdiction in Indian Country (CJIC) examination with a score of 70% or higher.3

The Tribal Law and Order Act of 20104 shifted primary responsibility for delivery of CJIC training to DOJ.5 Course development and responsibility for CJIC training have been assigned to DOJ’s National Indian Country Training Initiative (NICTI). The NICTI was launched in July 2010 to ensure that DOJ prosecutors, as well as state and Tribal criminal justice, social service, and health care personnel, receive the training and support needed to address the challenges relevant to Indian country investigations and prosecutions. The NICTI is located at the National Advocacy Center (NAC), a nationwide training center operated by the DOJ in Columbia, SC. The NAC is the premiere federal training institution for teaching legal and leadership skills to DOJ personnel and the broader government community. The NICTI hosts residential courses at the NAC each year, prepares and delivers distance education products, and authors and disseminates written educational materials. In addition, the NICTI Coordinator teaches at many Tribal and federal events every year. Since NICTI’s inception in 2010, over 21,600 personnel have been trained through NICTI-hosted training. The numbers have increased since COVID and NICTI’s incorporation of webinar training, which has increased training accessibility.

The CJIC training curriculum covers such topics as search and seizure law, criminal jurisdiction in Indian country, federal criminal procedure, the Crime Victims’ Rights Act, and investigating sexual assault, domestic violence, and child abuse crimes occurring in Tribal communities. Following two full days of lecture, CJIC students take a 50-question test.

Before the pandemic, the CJIC class was typically hosted by United States Attorney’s Offices (USAO). In a typical year, roughly 15 classes were held with approximately 500 officers in attendance. Unfortunately, in March 2020, all in-person CJIC classes ended due to the pandemic. On July 9, 2020, the United States Supreme Court issued its opinion in McGirt v. Oklahoma.6 In McGirt, the Court held that the land within the boundaries of the Creek Nation’s historic territory remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Therefore, it was critical that hundreds of officers in Oklahoma quickly receive the training that would allow them to pursue getting an SLEC and the ability to enforce federal criminal statutes. Accordingly, the NICTI was called upon to develop an online version of the CJIC class. All of the individuals attending a CJIC class should be working in or with Tribal communities or with Indian people. One of the criteria for being accepted into the class is that the individual is employed as full-time law enforcement.

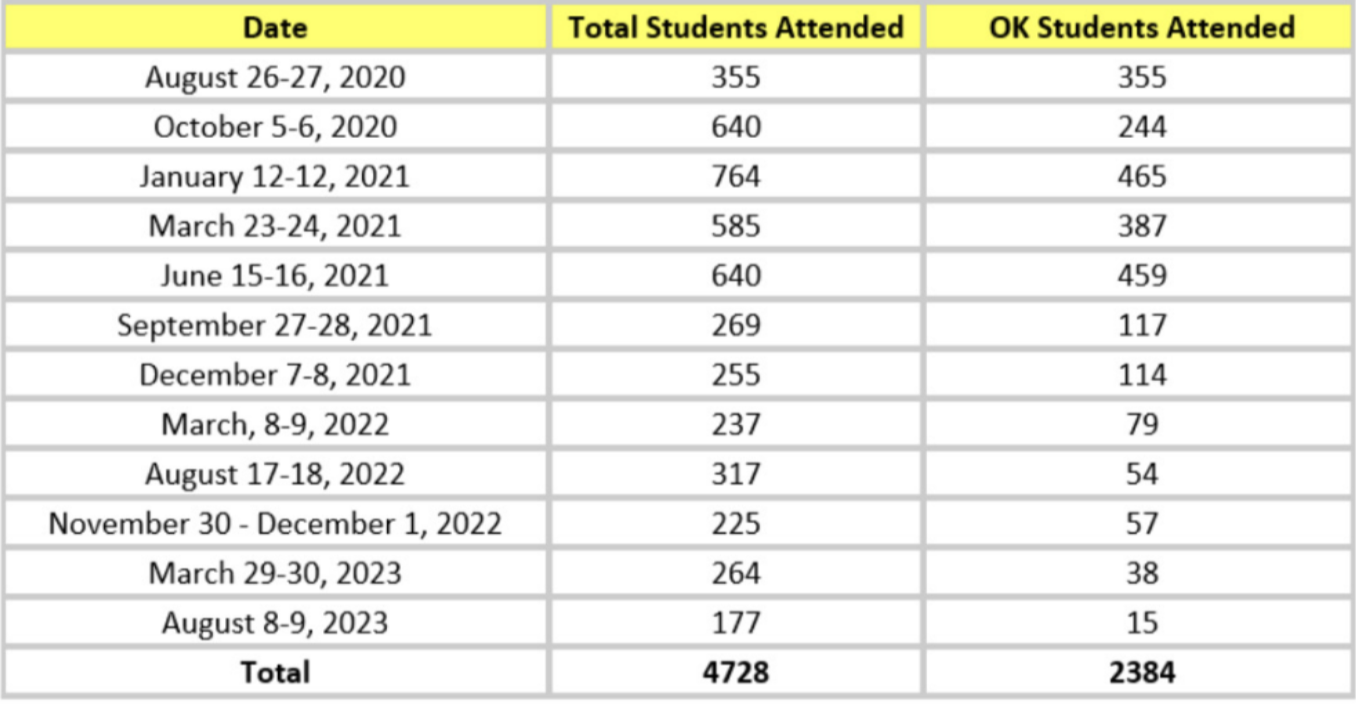

The CJIC class is now virtual only and is held approximately three times per year. The graph below illustrates the dates of CJIC training offered by the NICTI, the total number of students receiving the training, and the number of state, local, and Tribal officers in Oklahoma who attended the training.

It is very important to remember that not every officer who has taken the CJIC class now holds an SLEC. In September 2019, then-OJS Director Charles Addington issued a memorandum stating that completing the CJIC class is one way for Tribal police officers to satisfy the BIA Basic Police Officer Training certification requirements. There are other reasons why an officer who successfully completes the CJIC class may not get an SLEC. The primary reason is the failure of the applicant or the Tribe to submit a completed SLEC application package to the BIA. A second reason is the Tribal police department not completing the deputation agreement with BIA. A third reason is the lack of an adjudicated background investigation for the officer seeking the SLEC.7

An SLEC, once issued, can be revoked or suspended for cause. Termination can happen when an officer is fired or resigns his or her position, there is a sustained allegation or serious misconduct, or there is a finding that the SLEC was misused. An SLEC is good for five years. An officer holding an SLEC will need to reapply within 90 days of the expiration of the SLEC. An officer seeking a renewal of his or her SLEC will need to retake the CJIC class.

Holding an SLEC is beneficial to a Tribal or local police officer in several instances. An SLEC officer acting under the authority granted by a Deputation Agreement and within the scope of his or her duties shall be considered an employee of the U.S. Department of the Interior for purposes of:

- 5 U.S.C. § 3374(c)(2) (coverage under the Federal Tort Claims Act)

- 18 U.S.C. §§ 111 and 1114 (assault and protection of officers)

- 5 U.S.C. §§ 8191- 8193 (compensation for work injuries)

For example, if a Tribal police officer and SLEC holder is arresting a defendant for a federal offense and is assaulted by the suspect, the USAO may then be able to charge the offense of Assault on a Federal Officer.9 And if the officer suffers injuries, he or she may be eligible for compensation. It is important to remember that these protections apply when an SLEC holder is exercising federal authority. So, if a suspect assaults the Tribal officer during an arrest for violating the Tribe’s criminal code, these additional federal protections likely will not apply. However, there are different holdings among federal judicial circuits, so it is best to consult federal case law in your jurisdiction if there are questions.

The SLEC program provides Tribes with an additional justice tool if they choose to use federal laws to hold offenders accountable in Tribal communities. The training is free and easy to obtain now that it is virtual. If a police department does not currently have an SLEC program and is interested in starting one, they are encouraged to contact their BIA Special Agent in Charge (SAC). The regional BIA SAC controls the deputation process. One important caveat is that current law and federal regulations concerning SLECs specifically include the term Indian country. So, currently, Tribes in Alaska are likely unable to initiate an SLEC program until there is a change in law and federal regulations.

2020 through 2023. / Table courtesy of Leslie A. Hagen.

- 25 U.S.C. § 2804 (Pub. L. 101-379), 25 C.F.R. Part 12

- on.doi.gov/3F18aC2

- Id.

- Pub. L. No. 111-211, tit. II, 124 Stat. 2261 (2010)

- 25 U.S.C. § 2810(7)

- 140 S.Ct. 2452 (2020)

- Supra at 2.

- Id.

- 18 U.S.C. § 111